Working Together: Lessons Learned From a Small Business Partnering With a Large Prime

I just got back from a trip with a client (we’ll call them Small Co) exploring a potential partnership with a large Prime(Large Co). Small Co’s company is an emerging technology business in the dual use technology space. Their product is excellent and has gained significant traction over the previous five years. When I met them, they were four people living on a dream, some investment, and a lot of energy drinks. Now, their team has grown tremendously and generates nearly $10M per year in revenue. Smart management, aggressive investment, and relentless execution have made their product excellent, well-differentiated, and very well positioned to capture a large market share within their segment. We worked hard for months securing initial relationships and ultimately the opportunity to assemble a suitable gathering of decision makers within the prime for us to update them on our progress and find projects to work on together.

We scheduled a two-day event, with the first half of day one intended for an extended product demo, followed by project scoping. The morning of day two was for wrap-up and final discussion. We were all set- excited to go forth and bring home a win for ourselves, our prime partner, and our country. This is the stuff that gets me out of bed in the morning – doing well by doing good

At the end of day one, everything was great. Everyone was positively vibing, right until it became clear that some critical(and mutual) miscommunications had occurred that led us to believe this would be a short-term funded opportunity with a pipeline to more and led them to believe immediate funding wouldn’t be necessary, but they could work toward getting funding for specified development efforts in the future. Nonetheless, we mutually agreed our companies are perfect for each other, including on near term, high value opportunities.

The team left dejected, but I left elated. As I debriefed with the CEO, I discovered several areas of misaligned and unrealistic expectations. They form the basis of a few goals, framed here as questions I’ll use to prepare clients for future engagements.

Goal 1: Are our strategies and methods well aligned?

It seems obvious, but both companies must have aligned strategies and goals. Large primes live and die on large contracts delivering complete integrated solutions to large problems. Small technology companies can’t begin to deliver at that scale (though we’re working on changing that) but can provide high quality products that solve major aspects of the larger problem or create a differentiated product within a semi-commodified space.

In our case, the two-day event left everyone concluding our small business both solved a major aspect of the problem and created a differentiated product. More importantly, our product has a long runway of future growth, making it an enduring differentiator. For a high growth company looking for scale, that’s a huge win. We’re set to bring value to the prime and our customers for years.

Goal 2: Are the people involved engaged, knowledgeable, trustworthy and easy to get along with?

Many small businesses are rightly concerned about protecting intellectual property from theft or misappropriation. Another issue is whether the prime will hide you in a closet or make you a star within your sphere. Lastly, I’ve seen many companies work diligently to win large efforts for primes only to discover the workshare was a fraction of what they hoped.

Here lies two truths: First, no piece of paper will protect your business from duplicitous, nefarious people. Second, you therefore must do what you can to establish reasonable boundaries but ultimately must make a decision about whether you trust the people you’re working with. In a very large business, that gets very difficult simply because there are lots of people, incentives, and the march of time at play.

Here again, I saw tremendous victory in reviewing our event. The prime brought their technical team, their capture team, their business developers and their strategists. We brought the same. We asked each other the tough questions – what patents did we each hold? What technologies were built vs. envisioned? What competitive solutions were the prime already using? What firewalls did they have in place to protect our interests? What did they view as our strengths they couldn’t duplicate? What would they build themselves? Why?

The specific answers mattered, but what was important was the degree of transparency the prime gave us. Did they play their cards close to their chest or tell us sensitive things about themselves and their competitive position? When we disagreed on a point, were we treated with respect, fairness and openness to being wrong or with disdain and dismissiveness?

Likewise, our prime was evaluating us. The nightmare scenario for a prime is a critical sub that falls on its face, leaving them to pick up the pieces. A critical element of a large contract can lead to massive financial losses that upset shareholders, end careers, and create negative headlines. It’s critical small businesses in government technology recognize their responsibility to not just deliver with excellence, but with humble recognition of the critical role compliance plays in protecting primes and ultimately the public interest.

As often as I’ve heard of small businesses feeling cheated out of workshare by primes, I’ve heard of primes complaining of small businesses that weren’t ready for the spotlight and lacked the maturity to understand the role and value of bureaucracy and process, let alone the role and value of a prime integrator in ensuring the total solution meets government requirements. As much as I am an advocate of small businesses, I suspect there are more immature small technology companies than there are nefarious program managers in large primes. We made sure to bend the knee with humility and respect, even while we proudly advocated for ourselves and the unique value we presented

What we found was a team that was open, transparent, and honest. We met enough people to get a feel for the dynamics and internal politics we’d work within and a sense of what the future would look like. We left liking their team and the strong feeling that it was mutual.

Documents create boundaries but boundaries can be broken. Trust moves mountains. We left with real trust in each other- a huge win.

Goal 3: Are we ready to work within their system?

Oof. Here’s where the frustration happened. Long story short, there were lots of conversations with lots of people leading up to this meeting. Principals within small, high-growth technology businesses are stressed, tired, and (if we’re being honest) out over our skis engaging in conversations we have little expertise or experience in. Large businesses have lots of people doing lots of jobs, often with significant overlap.

Between a startup making promises based on hoped-for progress semi-dependent on variables beyond their control and Large Co employees confusing personal opinion for well-considered company position, we all got sideways. Small Co wanted a small pilot with funding and quick execution, Large Co wanted a working relationship to pursue work with.

Here’s the thing I’ve learned about being agile within a bureaucratic system: demanding the impossible is, well, expecting the impossible. If you expect the impossible you should expect to be disappointed. Flipping your perspective to the other person, you’re being unreasonable and I’m at best feeling inadequate but more likely attacked and disrespected.

I have two rules with two maxims for working through a bureaucracy: 1. Assume honesty and genuine alignment of strategy and objectives exist in your counterpart. Work with what a mentor calls “happy persistence” when faced with resistance or hesitancy. Asking for the impossible is putting your counterpart in an untenable position, which means you’re just being a jerk. At best, they feel inadequate. They more than likely feel attacked. 2. Realize this is a stakeholder management problem. As the same mentor says: “move like water around the rocks. Find the path of least resistance.” Either take what you can get and move on to the next stake holder or thank them for the conversation and walk away.

Once you’ve verified the person is on your side, figure out what they can give and choose to be happy with it. Work together to figure out who can give you the thing you all need and the best way to get it. Set down clear tasks with deliverables and deadlines. Follow up. Ask for warm intros. Follow up. Find your way to what you need, embracing the reality that enterprise sales are hard, and this is what it takes – every time. If you’re not willing to do that with a smile, find someone who can, or stop wasting everyone’s time. This is why, once you’ve established product-mission fit, sales is a career field supported by the CEO, not a CEO responsibility.

In this case, Small Co’s CEO’s role was to determine the strategy and requirements – we want to work with you, but we won’t do it on the mere promise of money. They did that with calm strength –perfect. Large Co’s leader had a job to do – work within their system’s constraints to achieve their goals. He laid those goals and constraints out with professionalism and empathy without apologizing for his reality - perfect. My role, as a sales professional, is to find and broker the deal. We found a mutual opportunity that will be easy for us to support, giving both sides tangible value without asking the impossible. We didn’t ask them to short circuit a complex funding allocation system and they didn’t ask us to spend significant resources pre-integrating an excellent product for a specific opportunity. On the flip side, the work we will do is easily reversed if our champion doesn’t make significant and tangible progress toward funding quickly. We all got most of what we wanted and preserved our relationship.

Final Consideration: Growth is Measured in Opportunities Before It’s Measured in Revenue

As I wrapped up our debriefing of the week, I described this arrangement to our client and said “You seem to feel this week was a failure. You’ve spent a lot of money, swore off opportunities, and added to your overall workload and don’t have funding to show for it like you’d hoped. If six months from now we hold a large portion of a large, high-profile contract, will you view this as a waste? More importantly, if before coming here we had this as the best outcome possible, would you have still taken the meeting?” The answer was clear: this week was well spent and an enormous success. We’d absolutely do it again.

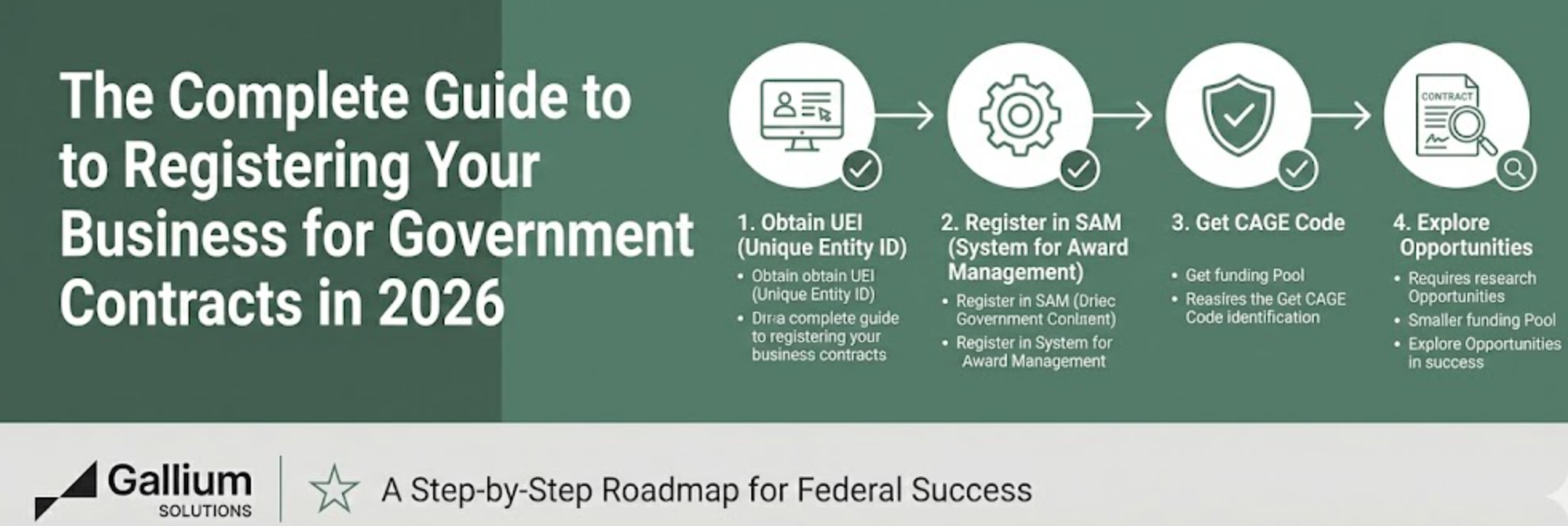

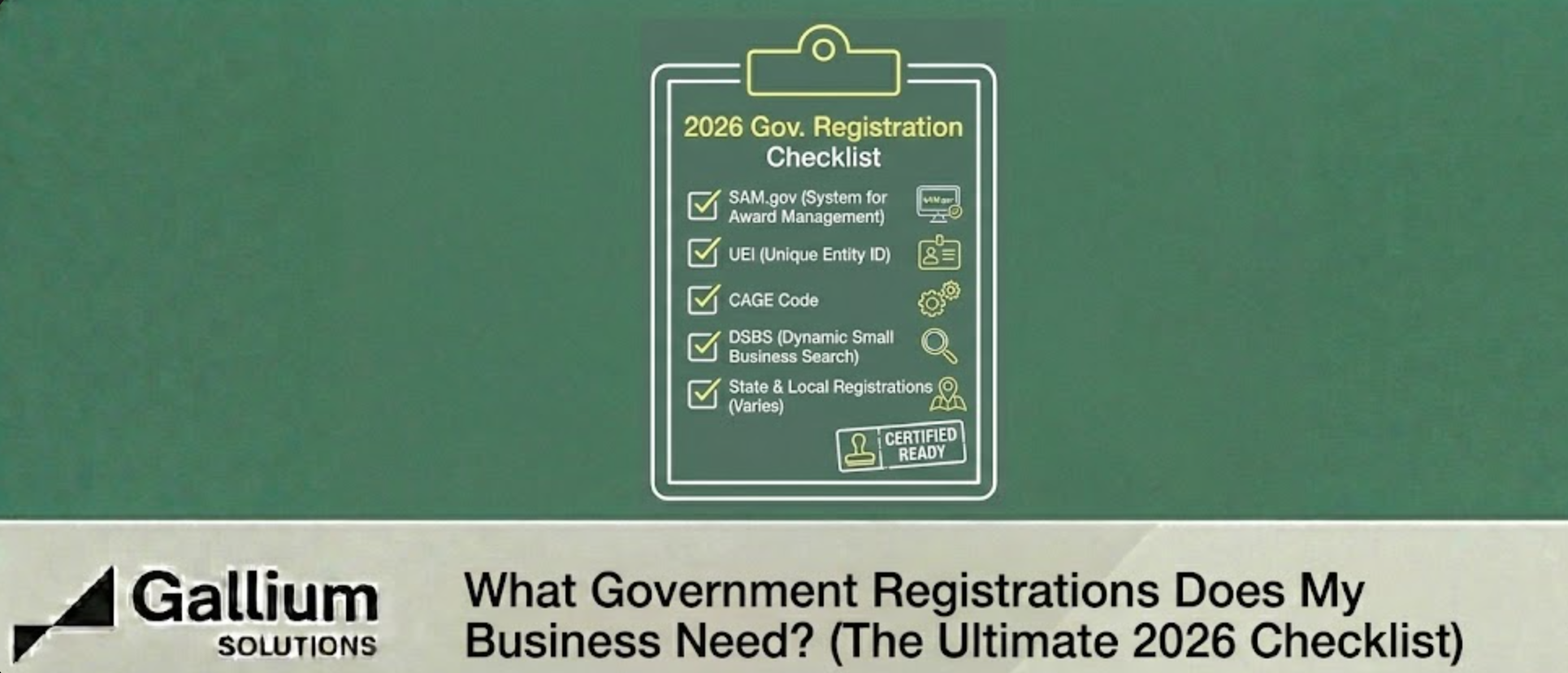

Unsure about how to source, vet, and apply for the government funding opportunities that are right for your business? It's what we love to do and we're here to help. To learn more about how Gallium Solutions helps you craft proposals that will catch the attention of the funders you need, fill out this form, and we'll be in touch!